The Portrayal of Witchcraft in Art: A Journey Through Time and Context

Witch hunts, Caliban and the Witch, The Library of Esoterica, and John William Waterhouse.

Witchcraft, an enduring and enigmatic subject, has fascinated artists and audiences for centuries. The portrayal of witchcraft in art has evolved through time, reflecting societal attitudes, fears, and fantasies. From the mythological enchantresses of ancient stories to the modern-day interpretations of witchcraft, the depiction of witches in art reveals much about the cultural and historical context in which these works were created. This article explores key representations of witchcraft in art and society, examining how these portrayals have been shaped by and have influenced societal perceptions of witches and their craft.

Historical Context: The War on Women

Throughout history, the image of witches in art has been one of malevolence and dark magic. The frenzy surrounding witchcraft began in the mid-fifteenth century in Europe, quickly escalating into widespread witch hunts. Women who didn’t conform to societal norms – those who were dishonoured or embraced their sexuality – became targets of these brutal persecutions. Between the 16th and 17th centuries, around 80,000 individuals, primarily women, were executed as witches in Europe alone.

Misogyny played a significant role in this tragic chapter. Authorities instilled a fear of women's power in men, deepening the gender divide. Terms like 'epidemic' were used to frame witch hunts, masking the true nature of these crimes. Existing prejudices against women were exploited, making it easier to scapegoat them for society's problems.

The Church was instrumental in crafting the image of women as diabolical. Superstition was rampant during the Middle Ages, and the Church linked women’s supposed social inferiority to a susceptibility to malevolent forces. This campaign reached its peak with Heinrich Kramer and James Sprenger's Malleus Maleficarum (1487), a text that demonised women and suggested that their very nature was inherently faithless. This book heavily influenced the visual and cultural representation of witches during this time.

Witch hunts were driven by more than religious fervour; they also had political motivations. The Roman Catholic Church defined the characteristics of witches and spearheaded their persecution, like their earlier crusades against heretics. Without the Church's long-standing misogynistic campaign, the witch hunts might never have reached such terrifying heights. The executions were carried out primarily by the state, allowing the clergy to avoid direct involvement in the bloodshed. The cooperation between Church and state marked one of the first political unions of the new European nation-states.

The sexual politics of the witch hunts evolved dramatically during the 16th and 17th centuries. Previously, the devil was a figure of ridicule, easily thwarted by holy water and scripture. However, as the witch hunts intensified, the devil's image transformed into that of a powerful master, with witches as his subservient brides in a twisted parody of marriage. This shift underscored a societal push towards male dominance, further entrenching the fear and subjugation of women.

Men, influenced by this propaganda, were taught to view women as dangerous and emasculating. Efforts to save accused women were rare, and the propaganda effectively divided the population. In England, for instance, there was no significant male-led opposition to the witch hunts. The enduring legacy of these dark times serves as a stark reminder of how fear and prejudice can be weaponised against the vulnerable.

Caliban and the Library of Esoterica

Silvia Federici’s Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation, 2004, meticulously examines the historical subjugation of women under capitalism. Federici traces the roots of gender inequality from medieval peasant revolts to the orchestrated witch-hunts by church and state. Her central thesis argues that the control over women’s bodies and reproductive rights was a deliberate strategy to oppress the working class and consolidate power.

Federici provocatively challenges readers to reconsider femininity not merely as a cultural construct but as deeply entwined with class relations, shaped by the manipulation of labour divisions under emerging capitalist systems. She reveals how historical events like the Black Death and subsequent labour migrations disrupted societal norms, leading to heightened control over women’s autonomy by religious and political authorities.

Despite the focus on reproductive roles, some critics note the potential overshadowing of other dimensions of women’s contributions and struggles. However, Federici’s work powerfully illustrates parallels between historical and contemporary gender dynamics, emphasising ongoing struggles for reproductive rights and economic justice.

In contrast, Witchcraft from The Library of Esoterica, 2021, offers a lush visual and narrative journey into the global history and cultural perceptions of witches. Curated by prominent voices like Pam Grossman and Jessica Hundley, this volume presents over four hundred artworks and essays that portray witches not only as persecuted figures but also as symbols of resistance and empowerment.

The anthology surveys how witches, historically scapegoated, have transcended folklore to become potent symbols in popular culture. From fairy tales to modern TV shows, witches have captivated imaginations and challenged societal norms. This collection reframes the narrative, depicting witches as resilient figures who defy conformity and embrace their connection to nature and spirituality.

Beyond its cultural insights, Witchcraft invites readers to reflect on broader social dynamics, illustrating how societal fears and prejudices against strong, independent women have historically shaped perceptions of witchcraft. By celebrating the courage and wisdom of these women, the essays in Witchcraft advocate for a nuanced understanding that rejects stereotypes and embraces empowerment.

Circe Invidiosa: Waterhouse's Enigmatic Sorceress

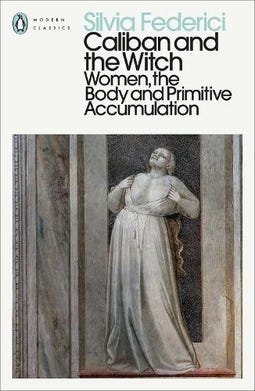

Circe Invidiosa (1892), Latin for ‘Jealous Circe,’ is an exquisite oil painting by the renowned English painter John William Waterhouse. Initially recognised for his contributions to the Academic tradition, later famously embraced the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood’s distinctive subject matter and artistic style.

Circe, the daughter of Helios, the Greek god of the sun, and Perse, a water-nymph, is a figure of immense power and allure. Known for her mastery of herbs and potions, she famously transformed humans into pigs, wolves, and lions. One of her most well-known tales involves the Greek hero Odysseus, whose men she turned into pigs upon their arrival on her island, Aeaea. However, Odysseus, protected by an herb given to him by Hermes, compelled Circe to restore his men into their human forms – a story immortalized by Homer in the Odyssey. Circe Invidiosa, however, draws inspiration from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, weaving a different narrative spell.

In this painting, Circe stands as a towering figure, radiating an aura of menace and unease. Her head tilts forward with intent as she poisons the water beneath her, poised to transform her rival Scylla into a grotesque sea monster. This act of vengeance stems from Glaucus, a sea god, spurning Circe’s affections in favour of Scylla. Beneath Circe’s feet, the bubbling shapes of Scylla’s transformation are already emerging, marking the irreversible change wrought by jealousy and spite. The viewer is drawn into the secluded grotto where Circe enacts her dark ritual. It is not Scylla’s transformation that captures the viewer’s attention, but the grave determination and palpable jealousy etched on Circe’s face—emotions so vividly rendered they seem to wrap around her like a cloak.

In exploring the portrayal of witchcraft in art and society, we journey through a tapestry woven with historical context, literary interpretation, and visual symbolism. From the early modern period's cautionary depictions to modern reinterpretations of empowerment, art has served as a mirror to societal perceptions and fears surrounding witchcraft.

Throughout history, artists have not only captured the external manifestations of witchcraft but have also delved into its deeper, metaphorical meanings—reflecting issues of power, gender, and the supernatural. From the haunting realism of Goya's Witches' Sabbath, 1798, to the contemporary subversions seen in feminist art, each representation offers a glimpse into the evolving narratives and perceptions of witches.

Books such as The Malleus Maleficarum have not only shaped public perception but also influenced artistic interpretations, embedding fear and fascination into the visual lexicon of witchcraft. Concurrently, contemporary literature and media have challenged traditional portrayals, reshaping the narrative to highlight themes of resilience and rebellion.

As I conclude this exploration, it becomes evident that the depiction of witchcraft in art transcends mere superstition—it serves as a reflection of human complexities, societal anxieties, and the enduring struggle for agency and identity. By engaging critically with these artworks, we not only unravel the layers of history but also confront our own perceptions and prejudices.

In essence, the portrayal of witchcraft in art is a testament to the enduring power of visual storytelling—a potent brew of history, imagination, and cultural critique that continues to captivate and provoke thought.

Image Source:

Witchcraft: The Library of Esoterica & Caliban and the Witch courtesy of Amazon.

Circe Invidiosa courtesy of Fine Art America